“There’s been a stabbin’” – Johnny Rotten

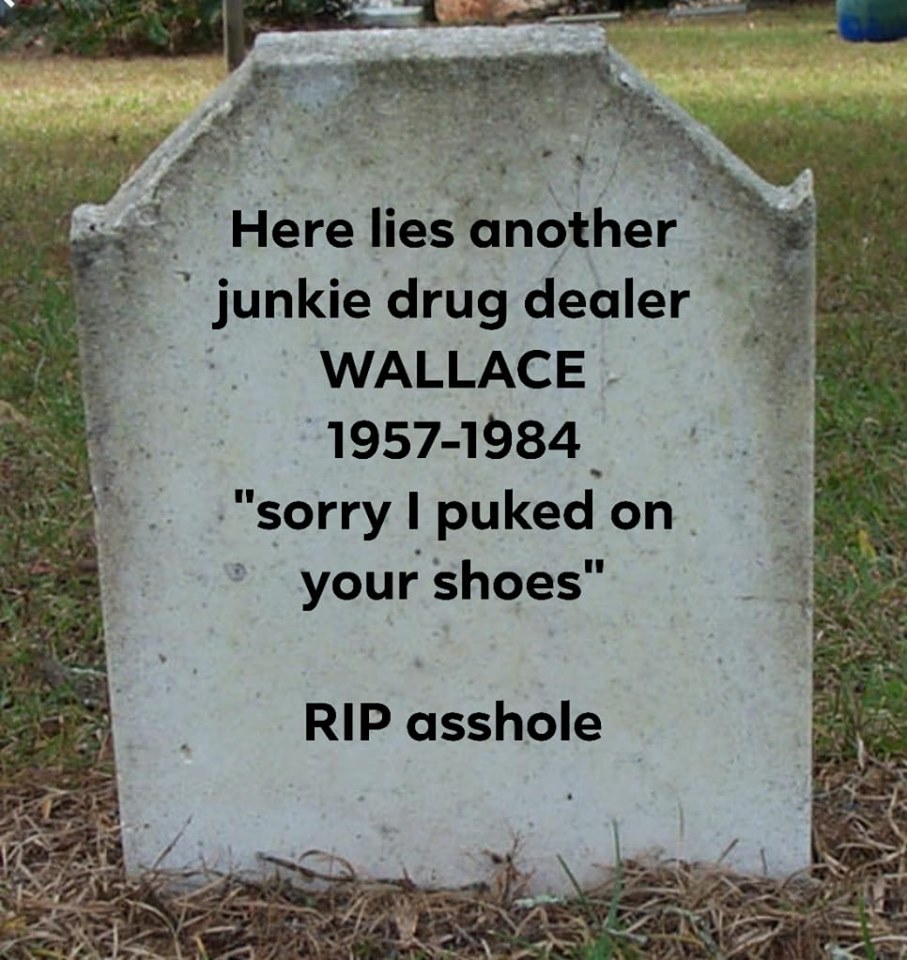

THE EPITAPH

It was long after supper and the dark of fall was everywhere that Saturday evening. There I was, arguing with missus over the phone in the kitchen.

The long-term recovery centre dealt with hard cases usually referred by word of mouth from former residents. It was privately funded, the result of passionate people reaching out to those who didn’t quite fit into usual facilities. I was still waiting for a conventional treatment bed somewhere after a decade of progressively harder drug use. She was already in a local 30-day program. I didn’t like being separated from her but advice at the time was that each of us should be treated on our own.

Trusting their counsel went so far against the grain in me by this time in my life, it took a huge leap of faith to go along with the set up. Sure enough, I had just wriggled out of her that she was off to the movies with some residents of her group—including a particular young single guy that she had befriended. I was not impressed.

In my raw emotional state this was the worst of news. My jealousy was doubly compounded by the inability to be with her and by my wait for a suitable bed. Of course, I was afraid of losing her, but I was a long way from admitting that out loud or even, to myself. I slammed down the phone in frustration. Looking around defiantly while others stared at blank walls or the ceiling without saying a word to stay clear of my dysfunction, I walked loudly out the door and into the night air.

The area around the James Street residence was a mixture of older brick homes built around the turn of the 20th century. Most had been gentrified by now, their red and brown bricks pressure washed of decades of paint and restored to their natural, if worn, condition.

Stoops and porches had been upgraded to cedar or treated wood for the most part, but the vestiges of its charming past remained in arched windows, decorative gingerbread trim and various architectural flourishes from the times. Narrow driveways separated some of the houses, the small lots and two and three storey heights of houses made them seem skinny.

The first place I ever rented of my own at the age of fifteen was a couple of blocks down, a place I remember well. It was $13 per week in ’72-73, a furnished room which came with a single burner tabletop stove but no fridge. In winter, I kept my milk up against the window to keep it cold. I mostly survived on Clark’s stew, peanut butter, and bread, that sort of thing. Sometimes I’d have to kick the communal bathroom door open in the middle of the night and evict sleeping winos from the tub and floor so I could use the facilities.

Each week, on Wednesdays, I’d panhandle the bus fare out in front of the Gilmour tavern so I could get to my parents place. My father had decreed that I get ten bucks per week until I turned sixteen. Wednesday was payday and I collected every time, thinking it was at least a way to remain in contact with my family. I’d go all the way there, get my stipend, be generally shunned by the rest of the obedient siblings who feared him, and leave.

Time since then seemed like a lifetime away on that Saturday night, though it only was a decade and a half later. This area once infested with rooming houses populated with speed freaks and hookers, the sickly and the poor, was now highly sought because of its proximity to downtown and government offices. Yet the neighbourhood reflected a kind of seediness too, and the residents were in a way cautious and reticent.

As I headed down the street, she called out behind me, asking that I wait up for her. She had followed me out of the house and was the only one either brave enough or who cared enough to check on me. She was my ex, a gal with whom I had had a five-year relationship but whom, after our breakup, had taken up with an old friend. Or maybe before, it long since didn’t matter. If I sent her to Amsterdam to body pack heroin back to Canada, I couldn’t very well complain that she might get distracted by her handlers.

In fact, I got married because I thought it might impress the judge and help me avoid a longer prison sentence a few years back and it was these two who had witnessed my ceremony. I remember sending the missus out in a snowstorm the week before to walk to the courthouse to get the license while I stayed in bed nodding off. The day of the wedding, we woke up late, shot heroin, picked up our witnesses in cab and headed off to get married. We then dropped them off afterwards and went home. It was as perfunctory as that. Obviously, though she said she didn’t care, it was no way to treat a lady.

Just a year or two older than me, my male witness and de facto best man was one of my old dealers and users in arms who had gotten straight a year or two ahead of me. Generously pulled strings to get me into the residence he worked at, the place he credits with saving his life, my ex had followed him in soon after. Out of gratitude, she volunteered at the centre the odd evening. While I was there, she especially looked in on me to offer encouragement.

I hardly noticed the attention; my life was so in flux that I had little time for considering the past. I remember feeling ambivalent when one day she suddenly apologized for everything that had gone bad between us. Perhaps I had lost the capacity to feel by then, but I recall being perplexed at the gesture. I don’t think I considered returning the favour and sweeping my side of the street as I thought her gesture unnecessary. While our time together was tumultuous, we remained on good terms. She and her man were surprised I made it to recovery alive. I suppose, so was I. It was my time to finally get straight.

She caught up with me and reached out with an understanding and concerned tone. She knew my anger, but she was different now than when I had known her. She was all the things she was when we had first met, and I had watched melt away in front of me. I could see her raw intelligence emerging from the fog of her previous life. Always striking, she had regained some of that classy look that made old ladies stop and tell us she reminded them of movie starlets from their youths. Jean Harlow was one they compared her with.

No sooner than I had turned to speak to her, out of the shadows appeared another old face from my life. He’d been lying in wait for me, having heard that I was in drug treatment. He was one of those freckled kids with reddish-blond hair and a wimpy demeanour. Thin, rat-faced, he had always been a plodder, not prone to great outbursts or loud behaviour. Nevertheless, he was a noted hash dealer, and, over the years, had become, at first a reluctant, but lately, a committed drug user.

He and I had a history that stretched back a decade. We knew each other when were both young pushers on the streets of Vanier, that one square mile francophone enclave perched on the banks of the Rideau River. It was just East of Ottawa’s Lowertown and across Beechwood Avenue from the high-class homes and embassies that surrounded the Prime Minister and Governor General residences.

We had collaborated on some deals, bought off each other at times, and I had even ripped him off once long ago. Later, after reconciling with each other, he, in turn, had returned the favour by fronting heroin from me and not paying it for it. As years passed, these minor transgressions became more serious.

If there is one thing you can count on in the drug world, it’s that as you age the consequences of your actions become more intense. Our street respect required that we step up our game of retaliation. That is why at some point I showed up at Larry’s door with a friend. We were let in and proceeded to rob him of a great slab of hashish.

So if we were keeping score, I was ahead. No one likes the tall poppy.

All he said to me that night after appearing out of the darkness was that we had unfinished business. I could see his skinny girlfriend lurking behind him. My ex was diverted by her, demanding to know what was up. I told him to go screw himself. I was in no mood to deal with him now and would have been happy to smack him around. Sure enough, we started to tussle.

I wasn’t worried about him physically, for as it was my adrenalin was up and running. There was nothing I could use better at that point than to lay a beating on this punk. I quickly assumed my usual fighting position with my left hand on his neck while proceeding to punch him repeatedly in the face with my right. Ducking so my blows would glance off his forehead, he kept trying to hit me in the stomach.

I remember thinking It was odd – for body shots weren’t going to hurt me as I was scoring better by pummelling his puss. I got off three or four quick ones before he managed to disengage and back off. He had a strange look in his eyes that puzzled me. His whole face seemed to go ashen and in contrast with the dark surroundings, almost eerily white in the dim light. He skipped backwards, nervously, and then took off running down the street.

Confused, I felt the trickle of moisture on my belly; looking down, I could see blood beginning to seep out of my mid-section. Clasping my hand on the wound, I realized he had stabbed me deeply even though I hadn’t felt a thing. The bastard must have used a pretty sharp knife.

The ex, bless her heart, saw I was in real trouble and turned around to go for help from the House ten or fifteen doors up. His junkie girlfriend, his partner in vengeance that night, tried to prevent her by blocking and threatening her. It was as if she wanted a matching foe. Either my assailant told her to get out of there, or she noticed him far up the street. Now realising she was on her own, the wench turned heels and ran away.

I went to the nearest house, rang a doorbell, and pounded on the door. The darkened doorway never lit up. Residents there would not open up despite appearing in the window. I told them loudly to call an ambulance as I had been stabbed. I wasn’t convinced they would. I turned into the street, more annoyed at my assailant’s gall than anything.

I looked up and down for my next option when the House van appeared before me. One of the senior resident/counsellors, a personable soul, a quiet and grateful ex-junkie from Montreal, was driver and the ex was in the passenger seat. He slid open the cargo door and after climbing in, I lay there on the floor slowing bleeding out.

The drive was predictably silent as we drove the few miles to the Ottawa Civic Hospital—perhaps because of the gravity of the situation. I almost thought he might be reluctant to help or be annoyed at the heat I would bring on the House.

I was one of those residents that came into treatment with my street personality intact. While committed to changing my life, that raw part of me permeated my every sentence and thought. I was aggressive and verbal, one of those guys who challenged everyone around me. I could argue a point to a stalemate if I thought it right. This at times annoys people to this day. After living by the laws of the jungle that is The Street, I knew that my alliances within the House at times would be tenuous, if not strained.

Looking back, I missed out on some great friendships, too caught up in my needs, my insurmountable marital woes, and my own interpretation of things. Whereas my saviour in the van that night was an amiable guy, capable and rugged, I was mostly full of it.

The bottom line is he saved my life that night at my ex’s call by coolly getting me to hospital. Had she not followed me outside, I would have likely died on the streets from whence I came. Her witnessing the event likely meant I’d be damaged but not finished off. As it was, I would have luck’s chance at survival because my attacker felt forced to leave it at that.

Knifing a junkie gangster is one thing but killing an innocent witness alongside them to thwart being testified against later is quite another. I was grateful they had let her go. I realized I was in trouble. A lot of blood was spilling out all over me from one three-inch gash. The blood was dark, black it seemed in dim light. I realized it had likely hit an organ. I knew all about the anatomy of wounds where I came from.

Just before arriving at the hospital, on Carling Avenue somewhere, she asked me if I wanted her to tell the missus anything, just in case. They were friends from back in her using days.

This caught me completely by surprise. I remember thinking: did something in my demeanour betray that I was unlikely to live? Or did they know something I did not? As if the fact that I was laying there as white as a ghost with a hole in me, or that she had likely seen my attacker withdraw his weapon from my gut before he turned and ran, or that the efforts of her and the driver now underway wasn’t enough.

It hadn’t really dawned on me at that point; my focus was very much on the moment. I searched for what to say and came up with what I expected was the right thing. I said to her to tell my wife I loved her and that should I die, to let my son know I was getting straight for him.

It sounds melodramatic now since it was as though someone had asked what your last words were without you realizing you were about to meet your maker. Which is precisely what it was. I was determined to hang on while now realizing it was no sure thing. It was sobering and I uttering those words were somehow a kind of admission that I might die. I said them but only out of duress, I remember thinking. Dying was bullshit.

They managed to get me into hospital and from there, a trauma team took over. In moments they had me on a gurney and had cut off my clothes. I remember the assembled team around me, all barking jargon-laden orders at each other. The main intern, a tall dark-haired resident, searched my face for signs of the severity of my injuries. Even in that position, I had a certain “what are you looking at?” feeling in me. I quickly realized that was inappropriate and, sure enough, here came the equalizer.

After ascertaining my immediate condition, he had pulled on a glove and told me succinctly he was going to probe my rectum to see if it was bloody. I recall thinking, sure, now that I’m laying here helpless you are going to stick your hand up my ass. Great, just what I needed.

No sooner had he penetrated me digitally, a great heave of vomit left me, completely over-shooting the crescent shaped dish being held at my drooling mouth. I saw the doctor jump back to avoid my expellant hitting his shoes, exclaiming as he did, a momentary look of disgusted horror flashing for a second on his face before returning to his regular expression of cool and calm concern. I heard the splat of whatever was in my stomach—supper mixed with bloody clots—hit the floor in front of him. I remember saying to him, ever my mother’s polite little boy, “Sorry for puking on your shoes, Doc”.

He looked at me strangely, seeming puzzled. He said that it was alright, almost reassuringly, as if inviting me to do it again, like I had no reason to apologize. But I did, and I felt the awkwardness of embarrassment at not being able to control my vomit. Everything then went dark as I fell unconscious.

I awoke the next day when the surgeon who operated on me came in to inspect his handiwork. He was a different guy than the fellow who had probed me rectally. He was the top surgeon the night before and he had been called in to rescue me.

Tall and thin, the touch of grey at his temples indicated to me that he was likely at the peak of his talents. This was all the more fortunate. He looked in shape. There was a bright intelligence in his eyes and warmth about him as he spoke to me without even a hint of superiority. When I asked what had happened, he said I died, and they resuscitated me. He told me he used something like nine pints of blood and bunch more plasma. He felt confident that he had stitched me all up, my stomach, part of my liver. He told me what to expect in recovery, when the draining tube should be removed and when I should try and stand.

But then, he did something unexpected: handing me his card, he tells me if I ever want to talk, to please feel free to call and come in and visit. He said he would make time for me.

What was with that, I thought. He was the head trauma surgeon; he had been called in by the attending resident whose shoes I had almost decorated the previous night and he had employed his specialty with finesse and a life-saving dexterity. He told me I had just a few moments to find life when he arrived but that I could live a long life now. But here he was… acting as if he was interested.

I was a gangster who deserved no compassion, and yet, he was offering me his time. I asked him to thank the staff in the O.R. and especially, the attending resident. I was still worried about those shoes. Later, I was able to thank them in person.

I soon had to face the nurses and their insistence that I stand and go to the washroom on my own. Once I had been shot through the chest and found that painful in a different way. But the 10-inch abdominal scar from north to south on my belly was infinitely more difficult. The draining tube left greenish-red pus that drained into a bag affixed to my abdomen. The rest of my dressings had to be re-done a couple of times a day.

I lost much weight, mostly muscle. But I survived, healed, and became very grateful. I didn’t even begrudge the guy who did the stabbing, figuring he was just doing what the street called for him to do. I reckoned this episode made us even once again.

The cops came in later that first day of recovery to enquire about who had assaulted me and start their investigation. They recognized me and simply turned around, muttering, leaving without so much as asking a question. “Oh, look who it is” they said and left. I’m sure my stabber had been counting on that.

I had been in the Civic Hospital before. Once, as I was withdrawing violently from heroin, my parents had gotten wind that I was there. My mother had showed up unexpectedly at my hospital door. It was in the isolation unit for some reason, probably in case the newly found AIDS virus or Hepatitis might be transmitted to others. She was her usual supportive self, but as a former nurse, in any case involving medicine she was scientific and pragmatic about what lay before her. She wished me the best and didn’t stay long.

My father, whom I could see lingering in the hallway, did not come in at first. He paced a bit outside my room door while Mom was visiting. I felt a vibe of some kind from her and I picked up on his unease. When Ma had finished, as usual without a negative word crossing her lips, she stepped out and in he came.

Dispensing with niceties, he addressed me by my full first name the way parents do when they are about to make a statement that is meant for the whole of you. He bluntly told me that if I kept up my lifestyle I would die. He said it in a matter-of-fact manner, if not a bit angry. He had already disassociated himself from me, that much was clear. His words were intense. And that he, and the whole of my family, he stated confidently, would simply wait for that day without any further worry. He said that when that inevitable time came, and surely it was not that far off, he claimed, they would then dutifully bury me. He promised right there that they would then forget me. For good. With that said, he walked out.

That was a few months before I made the final move to get straight by booking into hospital and recovery. But it always stayed with me, the brutality of his message, the finality of his condemnation, the way he was speaking for everyone else regarding their resignation over my fate. Could he do that?

It was my problem you see, how it affected others was not something that registered with me easily. I know now that it was of enormous help, and a great gamble on his part. He was wise and steeped with experience from a lifetime of helping drinkers in the military and elsewhere. Or maybe he’d just had enough of hearing his wife’s worries. I wouldn’t know.

I thought at the time I may just have to live to prove the old naval officer wrong, just out of spite (although I used more colourful language). I also knew he may be counting on that; however, the strength of his words, well, there was just no escaping them.

As I lay there in my hospital bed over the next few days recovering from my ordeal, I was struck with just how lucky I was. Even more, I thought of my father, my family, my wife, and my son. My life flashed picture by picture before me in its entirety, affording me the chance to glimpse its severe dysfunctions. The addiction, the prison terms, the criminal lifestyle, all the weasels and poseurs I had surrounded myself with.

More than that, my mind kept coming back to my last words to the trauma resident in the emergency. I thought that up until then, I had not amounted to much. Ten plus years carrying a gun, dealing drugs, and running a crew, eschewing most of the values my parents had instilled in me, becoming a reckless drug addicted menace to society. I had let down the lot of them. I suppose most of all, myself.

Any potential I may have had squandered like so much ill-gotten gain. Somehow, it came to me that those final words to the doctor in the emergency room as I skirted with death could have served as my epitaph. They would sum up my existence perfectly. It’s how I would be remembered most fittingly for the waste of humanity I had become.

I imagined a mossed tombstone, the dark sky of a cemetery, and overgrown weeds of neglect. No one was coming to visit my bones on the anniversary of my demise, or on a birthday, or ever. The coldness of the wind waters my eyes as I imagined looking upon my own burial place.

Well, that simply would not do…

© CKWallace, 2012, all rights reserved

Well, that simply would not do…

CKWallace

copyright 2012, all rights reserved

Advisor to Men